As you can tell by these fancy brocade duds, I’m a clergyman. But at heart, I’m an historian. I wound up in this vocation by my love of history. One of the things about history is that it’s written by the victors. History is therefore somewhat subjective. It’s always slanted. But every history has its dark side. From the pages of some obscure journal or other source, one can always find out what the vanquished experienced and from the stories of the victors and the vanquished, a more reasonable facsimile of the truth can emerge.

The American Revolution was a glorious cause. The tyranny and oppression of the British were over the top. The Revolution was long overdue. And yet, even our own Revolution had its dark side. We don’t hear about the atrocities inflicted by the Colonial Army. But they happened. They happen in every war, even for the most just cause.

King George III

I suspect none of us learned in our history textbooks in school how the Church of England in the Colonies suffered. It did. Greatly. Our textbooks omit the fact that not just a few Anglican churches and rectories were burned to the ground, frequently with the occupant inside, by the Colonial troops and the property taken. We hear nothing of the Anglican priest slaughtered at their Communion Tables or those dragged from their high, three tiered pulpits and hanged in the Church yard. We hear little about the throngs of Anglicans, laity and clergy alike, who abandoned the Church during the Revolution for the Presbyterian and newly forming Methodist churches because they no longer wanted to be associated with the Crown. It’s one of the reasons those denominations have always been larger than us.

But when the dust settled and the British had finally gone home, what had been the Church of England in the Colonies was in shambles. There had been really not much organization. The colonial Church had been a missionary district of the Diocese of London and now with those ties broken there wasn’t even that. There were no bishops; just a large mass of demoralized and frightened men.

These men, the priests of the Church of England, took their lives very seriously. Ordination in those days was a pain in the neck. After one had been duly educated at one of the universities, arrangements were made in the autumn for the ordinations to take place. In the spring, after the weather had gotten nicer, these men were put on board ships to make the long, arduous and boring journey across the Atlantic where they docked at Portsmouth or Southampton. There they were met by carriages which took them north to St. Paul’s Cathedral in London where that evening they were ordained deacon and the next morning to the priesthood. Then they were packed back up into the carriages which headed south again to catch the ships and the next high tide. No time for the Tower of London and Big Ben was still not even a dream.

During these ordinations, each candidate took an oath to the death to the King who was, after all, the head of the Church. It was a sacred oath, one not taken lightly and to which each candidate owed his honor and his integrity. This was an oath as important as their marriage vows and could never be broken.

Bishop Seabury

In 1784, the Reverend Samuel Seabury, Rector of Christ Church, Hartford Connecticut, intimidated the local clergy into electing him their bishop. Seabury was an arrogant somebody and somewhat of a bully who made the long trip across the Atlantic to be consecrated bishop. But when he presented himself with all the testimonials to his fitness to be a Successor to the Apostles, the Bishop of London asked him if he would take the oath of allegiance to the King. Seabury replied, “Well, of course not!” The Bishop replied, “Then I cannot ordain you.” Then under his breath, the Bishop said, “But I know someone who can!”

So, The Reverend Mr. Seabury made his way north to Scotland to the Bishop of Aberdeen, a Bishop of the Scottish Episcopal Church, not to be confused with the Church of Scotland, that bastion of Calvinistic Presbyterian heresy which is a whole other sermon in itself! The Bishop of Aberdeen agreed to consecrate Seabury, but on two conditions: 1, that the new American Church be named after the Scottish Church – “Can’t very well go on calling it the “Church of England,” now can you”; and that the new American Church use the Communion of Liturgy of the Scottish Church rather than that of the Church of England. This was actually a blessing to us all since the Communion Liturgy of the Church of England is rather strange – one receives Communion in the middle of the Eucharistic Prayer after the Words of Institution. Go figure. Archbishop Cranmer must’ve been having a bad day. In any event, Mr. Seabury was consecrated and returned to Christ Church, Harford, now Christ Church Cathedral, as the Right Reverend Samuel Seabury, Bishop of Connecticut.

The next year, the Reverend William White, soon to be the first man actually elected by the Church as bishop, called for a conference of what was left of the Anglicans in what had been the Colonies to assemble at his parish Church, Christ Church, Philadelphia, to hammer out what an American Church might look like. Christ Church Cathedral still stands to this day and is a vibrant, active parish in the old part of Philadelphia. It’s an old Georgian building with galleries around three sides, painted white inside with clear glass windows and box pews. It’s gone rather High Church in the last two hundred years. Wonder what Bishop White would think of that? In any event, on a hot, July day in 1785, as many as could attend, filled Christ Church: the clergy on the main floor, the laity in the galleries. The clerk of the conference writes that the first day was total bedlam: those who had taken up the Revolutionary cause vs. those who had remained loyal to the Crown. Of course, it was all very polite. For instance, one clergyman would rise to respond to another by saying, “I would like to respond to my beloved Brother in Christ, the Heretic and Traitor from South Carolina…..” This would be followed by applause and booing and stomping and cat calls. (So much for English gentility!) By the end of the day, soon-to-be Bishop White was at his wits end. Nothing had been accomplished except division and fighting.

Christ Church Cathedral, Philadelphia

And the next day was none the better. After Morning Prayer, the proceeding were take up from the previous day which immediately turned into yet another pie fight. And it got nastier. It wasn’t pretty and Bishop White was by now pulling his hair out. Violence had not yet ensued, but it was well on the way.

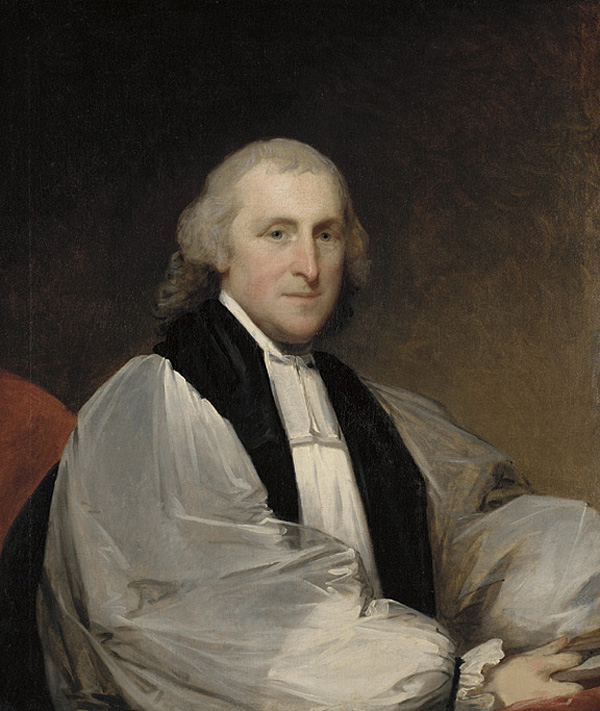

Bishop White

In the midst of this nightmare, the clerk handed Bishop White a note which said that the Reverend Mr. George Brown of New Hampshire wished to address the assembly. Bishop White must’ve thought, “What can it hurt?”

The Reverend George Brown was a nobody vicar from a small parish outside Concord, New Hampshire. He was short, fat and dumpy and beginning to go bald. While highly educated, he spoke with a stammer and was quite an introvert. But his parish adored him. What he lacked in physical attributes, he more than made up in abilities as a pastor.

Over the din, Bishop White yelled, “The Reverend Mr. Brown of New Hampshire has asked to address the conference.” Mr. Brown was seated in the back of the Church and began the long trek down the side isle, there is no central isle, of the Church. He bowed to the Communion Table and shook Bishop White’s hand and then began the long ascent into the three tiered pulpit. These pulpits were three-decker styled, the bottom for the “Clerke,” the middle for the Lay Reader and the top from which the sermon was preached. These were the days before public address systems and the pulpit was topped with a sounding board so everyone could, at least in theory, hear.

Mr. Brown looked out onto the sea of men in black and cleared his throat. He must’ve been petrified, but he mustered up some courage and began to speak: “August Gentlemen, I..” From the back, someone yelled, “LOUDER! WE CAN’T HEAR YOU!” That must’ve soothed Mr. Brown’s nerves! But he went on, a bit louder: “AUGUST GENTLEMEN, Fellow Clergymen, Laymen in the galleries, I have spent the last day and a half as a witness to these proceedings which have been painful and filled with much rancor. And I have searched the innermost workings of my heart to come to some resolution about the matter at hand. We are all men of integrity and high minds, now situated in what seems to have become a new nation. Some of us sided with the cause that has prevailed, all good men, men of integrity and pure heart. But I must admit that I have remained loyal to the Crown and continue to do so. I, as you, took a sacred oath, which in my own mind I cannot betray. And many of you have come to a different conclusion, one with which I do not agree, but which I honor, for you are all men of good will.

“But as I have sat and witnessed these proceedings, I have come to the firm conclusion that I cannot pledge my allegiance to Mr. Washington. And at the same time, I realize that I can no longer pledge my heart to King George. For neither George Washington nor George the Third took flesh of the Blessed Virgin and became one of us. Neither George went to the Cross and have his life for the sins of the world. It was Jesus. It was Christ himself who has called us, neither of the Georges, and it only to him that I can give my heart. And when I look at all of this in such a perspective, the rest becomes unimportant. And so I will continue a priest in whatever this Church is to be named, with only one oath, and that to Jesus Christ our Lord.” Mr. Brown paused, “I thank you.”

Mr. Brown descended the long staircase of the pulpit of Christ Church and began to return to his seat. And no one said a word. No one could. The only thing one could hear was the clopping of horseshoes against the cobblestone street outside. One could’ve heard a pin drop. No one coughed. No one rustled. Dead silence. And the silence continued for nearly five minutes – a silence filled with wordless awe and wonder.

After five minutes, Bishop White slowly stood and addressed the assembly: “Does anyone have anything further to contribute to this matter?” There was no response. Bishop White then asked them all to rise, opened the English Prayer Book and offered a collect, and then dismissed the assembly for lunch. “We will reconvene at two o’clock and take up the matter of a constitution.”

Tomorrow we will celebrate the 235th anniversary of the founding of this great nation. And much has changed in that time. We presently live in a nation divided, of anger and vehemence not unlike that assembly gathered in Christ Church on that hot July day of 1785. And we all think we’re right and we demonize those who might disagree with us. There is verbal warfare and adherence to ideologies that do nothing but continue to make things worse. And we all feel it to some degree. And we all have our opinions and our allegiances. Some of us are Republicans and some of us are Democrats. Some of us are screaming, left wing liberals and some of us are right wing conservatives. And I suspect if we took a poll in this Parish Church this morning, we’d find a mixed bag. And yet, the words of the Reverend Mr. Brown are as profound on this day as they were on that hot, July day so long ago. Because our true allegiance isn’t to the elephant or the donkey; it’s not to a cause for the left or the right; it’s not to a party or a person or even to the Church, but, as Christians, it is to Jesus Christ and to him alone. And when we are able to put things in such a perspective, then the Reverend Mr. Brown was right: the rest just doesn’t really matter.

We live in perilous times. If one watches the news, it’s not pretty out there and the future is one, big, giant question mark. We’re in a mess and there seem to be few viable roads out. But for us Christians, if we can keep in mind to whom we owe our ultimate allegiance and to whom we belong, then the future is not so daunting and in the midst of uncertainty and fear we can be beacons of light and hope not only to ourselves but to those who also need it. And if the worse happens, it will happen. And we will survive and thrive because we know who and whose we are.

So, tomorrow, as you slather your hot dogs with relish and salt your potato salad, and put on your parkas to go out and watch the clouds light up, give thanks for this great nation and pray for its future and its leaders. But, at a deeper level, remember to whom you owe your ultimate and willing allegiance. Remember who and whose you are. Remember the One who is our true and only hope; that One who, as the Reverend Mr. Brown said, took flesh of the Blessed Virgin and give his life for the world: Jesus Christ our Lord.

Amen.

WELCOME!

Welcome to my little blog of sermons and stories. I don't consider myself a "preacher." When I'm preached to, I fall asleep. zzzzzzzzzz. So do you! But if I hear a good story, I listen and chew on it until it sinks in. Kids tune out at lectures but they love stories...and we're all kids at heart.

So, set aside sin and guilt and all that institutional claptrap and sit back and revel in the love of God which has no strings attached. And always remember to laugh.

And for my sister and brother story tellers out there, remember plagiarism is the highest form of flattery. ;)

So, set aside sin and guilt and all that institutional claptrap and sit back and revel in the love of God which has no strings attached. And always remember to laugh.

And for my sister and brother story tellers out there, remember plagiarism is the highest form of flattery. ;)